20 Rewilding Lessons from Isabella Tree: Insights to Restore Our Planet

Reading time: 14 minutes

Restoring Nature: The Story Behind the Knepp Wildland Rewilding Project

A Bold Experiment in Nature Restoration

Knepp Wildland is a groundbreaking 1,400-hectare rewilding project in England that has, over two decades, challenged conventional approaches to nature restoration and introduced innovative strategies to heal our landscapes.

The project’s focus on nature restoration is not about bringing back or conserving a single species, nor about maintaining the status quo of a given landscape. Instead, its philosophy is about pursuing overall increases in the resilience and biodiversity of a landscape by surrendering human control over the area as much as possible and allowing nature to take its course.

At the earlier stages of the project, large keystone species where selected and introduced within the rewilding area boundaries. The idea was that the introduction of key herbivores may mimic the role that missing megafauna may have played in driving ecosystem dynamics thousands of years ago. At Knepp, free-roaming herds of English longhorn cattle, Tamworth pigs, Exmoor ponies, and deer shape water meadows, shrubland, and wood pastures through their natural disturbances.

This rewilding initiative has led to a remarkable recovery of wildlife, attracting endangered species like nightingales, turtle doves, and purple emperor butterflies. Knepp’s rebounding ecosystem is ultimately a story of hope, showing that nature can bounce back and heal itself if only we allow it to.

*Affiliate link: If you enjoy our content, consider purchasing your book through our link. We earn a small commission, which helps support the blog. In addition, 10% of all revenue generated is donated to charitable causes.

Why This Book on Rewilding Captured My Attention

This book promised to tick a lot of my interests, for instance in regards to offering new ways of thinking about how we can manage our land–particularly agricultural landscapes–to increase biodiversity. Are we still in time to slow and reverse the biodiversity collapse we are witnessing? Can we manage somehow to feed ourselves in a sustainable manner while contributing to land restoration?

Hopefully, some lessons learned from this British experiment could be applicable not only across different geographies but also across scales, from a landscape scale to someone’s small backyard, and can contribute to a better understanding of how we can successfully bring biodiversity back to our lands.

Deer in Knepp Wildland, Sussex. Photo by Ian Cunliffe © Copyright.

20 Key Rewilding Insights from Isabella Tree’s Knepp Wildland Project

1. How Agricultural Changes Devastated the British Landscape

Changes in land use, mainly related to agriculture, have dramatically altered the British rural landscape in just two generations. The proliferation of agricultural fields has led to the almost disappearance of flower meadows and grassland, the extensive clearance of wasteland and shrubland, and the draining and pollution of natural water courses and standing ponds. The numbers are soul-crunching: 75,000 miles of hedgerows lost since the Second World War, 90% of wetlands disappeared since the Industrial Revolution, or 97% loss of wildflower meadows since the war. England’s National Parks are regarded as “cultural” landscapes designed primarily for human recreation, and are very far from the USA’s National Park model, where the preservation of nature’s dynamics sits at its core. A recent ranking shows that out of 218 countries, the UK ranks 29th for nature depletion.

2. Embracing Self-Willed Ecological Processes for Nature Restoration

The key to Knepp’s success is the focus on “self-willed ecological processes”. Rewilding focuses on land restoration by allowing natural processes to unfold with minimal human intervention. Conventional conservation is about targets and control, about preserving the status quo, or about maintaining the overall look of the landscape. This type of conservation typically focuses on micro-managing a small habitat for the benefit of several or even a single species. However, the author argues that such approaches produce inferior biodiversity results, its landscape outcomes are fragile and increasingly vulnerable to external factors (e.g., to climate change), and that they also constitute a costlier approach overall. Isabella Tree beautifully defines rewilding as a leap of faith, of surrendering preconceptions and waiting to see what happens. It goes without saying that this approach challenges and unsettles scientists who like to test hypothesis, run models, and set goals. “The idea of constructing a computer model to identify the outcomes of self-willed land seemed like trying to predict the lifetime achievements of an unborn child”. Instead, rewilding has no specific goal other than the broad expectation of restoring land’s natural processes and of improving biodiversity. The biodiversity success at Knepp is evident, with hundreds of new species of birds, mammals, amphibians, and insects returning to the landscape just a few years after “letting go”.

3. Revealing Nature’s True Preferences Through Rewilding

Process-led conservation allows nature to reveal the limitations of our own understanding and the plasticity of species. We are trapped by our own observations: in a world completely transformed by humans, what we observe in nature is not necessarily the environment wildlife prefers, but more likely the depleted remnant that wildlife is left to operate with. In other words, animals described as preferring a given habitat may be just surviving at the limits of their natural range. The result of rewilding–of letting go–is unsettling, again, because it reveals how little we actually know about nature’s “true preferences”. The Knepp project, now the top breeding ground for purple emperor in the UK, has revealed that the purple emperor was previously considered a woodland butterfly only because that was the environment it had left to cling on to. However, this species shows a clear preference for sallow in the landscape, not necessarily for closed canopy forests. Numerous other misconceptions are brought forward in this book. The conclusion of these realizations are startling: we may be investing large amounts of conservation funds towards maintaining vulnerable populations in remnant habitats instead of trying to allow for “natural” ecosystems to emerge to which they may be much better suited.

Longhorn cattle freeranging at Knepp Wildland. Photo by PeterEastern © Copyright.

4. The Myth of Closed Canopy Woodland as a Natural Climax State

Closed canopy woodland has erroneously become synonymous with nature. In several European countries, there is a popular saying that in the distant past–before human-dominated landscapes emerged–a squirrel was able to cross the entire country from tree to tree without touching the ground. This common belief aligns with the dominant theory of vegetation succession, which suggests that land without vegetation is initially colonized by scrub before eventually giving way to trees. Once the trees have managed to take over the area will have then reached a permanent end state known in ecology as “climax vegetation”. The problem with this theory is that it overlooks the role of animal disturbance, a critical force of nature that works in opposition to vegetation succession.

Fossil records show that megafauna, such as the aurochs, tarpan, wisent, elk, European beaver, and others re-colonized Central and Western Europe about 12,000 years ago, shortly after the last ice age. In contrast, polen records show that the prevalent trees in todays forests only appear 9,000 years ago at the earliest, 3,000 years after the animal herbivores. The author argues that the fact that a closed canopy has become synonymous to reaching a climax state has more to do with humans wiping out these large herbivores from our landscapes a long time ago and therefore being, again, trapped by our own observations–thinking a closed forest is the final destination just because these animals are no longer there. Indeed, it is at the very least curious that a closed canopy environment may be considered a climax state, yet, at the same time, be demonstrably poorer in terms of biodiversity than meadows, pasture, heaths, and other farmland. Is this truly what we want to aim for with our conservation efforts? Similarly, the author argues that the presence of oak, Britain’s national tree, is proof that a closed-canopy environment is not the end state: oaks simply cannot regenerate under closed-canopy conditions and would be easily outcompeted by other species. This is a very interesting debate, which we will address in more depth in a future post.

5. How Keystone Species Shape Diverse Habitats

Animals are drivers of habitat creation, the impetus behind biodiversity. Without animals you have static and biodiverse-poor habitats with declining species. According to the author, it is more likely that, resulting from the balanced interplay between vegetation succession and animal grazing, a wood pasture would be more likely the climax state several thousand years ago before humans dominate the landscapes. Roughly half the plant species in Central Europe have seeds with hooks to facilitate transport by fur, indicating that they have co-evolved with animals. Reintroducing grazing animals–proxies of missing megafauna–and other keystone species such as the beaver can accelerate the creation of biodiverse-rich habitats at a very low cost.

6. Understanding the Importance of Evidence in Rewilding Efforts

Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. The author argues that this principle is often ignored, particularly by paleoecologists. It is notoriously difficult to come by fossil evidence, but when it does appear it often upends all pre-existing theories of animal distribution in certain areas. Britain was connected to mainland Europe just 8,000 years ago; would animals simply stop at Calais or is is more likely that megafauna present in Europe would also make its way to Britain? Britain is likely not the exception, and megafauna would also have been there–also supporting a landscape ecology more aligned with wood pasture.

7. Overcoming Our Intolerance to Natural Decay and Change

Modern society has become disconnected from natural processes like decline and decay, which are essential for maintaining healthy ecosystems. We have become accustomed to human-altered landscapes in the countryside, where clearing leaves in the autumn, removing dead trees from the landscape, or removing unwanted shrubs are examples of our preference for neat landscapes where we can walk our dogs while we sip our coffee. These small actions though interrupt nature’s cycle and exert large effects on the landscape: it impedes nutrient recycling and removes habitats for smaller creatures like insects, birds, and other animals that would come in their wake.

8. Cultural Challenges to Rewilding Projects

Rewilding projects often face important cultural stumbling stones. Unfortunately, sometimes it is not as easy as just letting go and sitting back to watch the process unfold. People have pre-conceived views of what rural landscapes should look like, even if this is just determined by what they remember from their childhoods or what they were told by their parents, or even preconceptions that date back to the Second World War. Of course, this preconceived preference for a given landscape has nothing to do with what biodiverse-rich landscapes look like. The Knepp project encountered a lot of resistance early on by neighbouring farmers, who simply struggled with the idea of leaving a piece of land “unproductive”, of not dealing with the weeds or scrub, or with bringing in wilder strains of grazing animals.

Photo by Richard Loader on Unsplash.

9. The Essential Role of Scrub in Natural Regeneration

Scrub is critical for natural regeneration. In the balanced interplay between vegetation succession and animal grazing, tree saplings need the presence of thorny scrub. Scrub acts as a nursery, providing the young trees with protection from herbivores and with sufficient light that is required for them to succeed. When grazing animals are removed from the landscape equation, vegetation succession progresses until the shade tolerant trees eventually win the game and produce mostly biodiverse-poor closed-canopy forests. Ironically, these are the ecosystems that are being funded for protection. Interestingly, Isabella Tree suggests that our preference for closed-canopy forests is deeply rooted in psychology and cultural perceptions, with its origins in our nineteenth century stories of Hansel and Gretel, Little Red Riding Hood, or Snow White–fairy tales from dark conifer forests of Eastern Europe. However, the very fact that scrubby species exist today proves they must have existed in the past–how then did they survive into modern times if our original landscape was a closed forest? Scrub is one of the richest habitats of the planet, but humans are prejudiced against it because we consider the land to be “unproductive”.

10. The Impact of Introducing Grazing Animals at Knepp

To facilitate the recreation of a more natural landscape, English longhorn cattle, Tamworth pigs, wild Exmoor ponies, and red and fallow deer were introduced in Knepp. Their disturbance now shapes water meadows, shrubland, and wood pastures, creating new habitats for wildlife. These animals change the landscape quickly in surprising ways. For instance, the pigs’ initial “capacity for damage” translates into a patchwork of pioneering plants appearing just a few days later. Invertebrates, including bees, then colonize the exposed ground, and other animals, such as wrens or robins, would then benefit from the increase in insects. Ant hills also emerge, thriving in micro-climates of sun-warmed, aerated soils. In turn, anthills attract mistle thrushes, wheatears, and green woodpeckers. Butterflies and lizzards also return. Anthills change the soil composition as well, creating a more alkaline soil that attracts different species of fungi, lichens, mosses, grasses, which then help to bind the soil surface. As illustrated, the disturbance created by the introduction of just one grazing species has huge cascading effects on the biodiversity of a given landscape.

11. Debunking the Argument of Food Production vs. Rewilding

Producing more food for a growing population is an erroneous argument often thrown against rewilding projects. It is an argument that is strongly routed in the subconscious of the rural population dating back to the Second World War: we must work every inch of our land to ensure our survival. According to the author, this is an argument also promulgated by the food and farming industry, which claims food production needs to increase by 70-100% by 2050 to feed an expected 10 billion people. However, this narrative clashes with the experiences of British farmers over the last decades (including the author’s), who have been consistently driven out of business by global markets–through low food prices resulting from subsidies and overproduction. The reality is that not only is there sufficient food, but a third of it produced globally is wasted each year. We do not only waste staggering amounts of food across every step of the food chain–from agricultural production to household consumption–but our meat-heavy diets means we inefficiently consume a lot more grain indirectly through the animals than would be necessary if we consumed it directly.

The same dynamics that threw Knepp out of its original farming business also affects a large part of marginal land in Europe. These dynamics are accentuated further by people wanting to move to cities. As a result, it is estimated that more than 30 million hectares of farmland in Europe will be abandoned by 2030–an area larger than Britain. Is there really not sufficient space out there for bringing back biodiversity, at the very least in these unproductive farming areas?

12. The ‘Shifting Baseline Syndrome’ in Landscape Perceptions

We look at a landscape and see what is there, not what is missing. What you see as a child growing up often influences what you want to continue to see. Nostalgia binds us to the familiar, and we erroneously believe that this landscape has been like this for centuries. It is not only the layman that falls into this trap, but also the expert. “Shifting baseline syndrome” was first coined by fisheries scientist Daniel Pauly, who noticed experts adopting a baseline similar to what they had experienced at the beginning of their careers, rather than considering populations in their original state. We should of course be aiming higher than the biodiversity and ecosystems found just a few decades ago.

Photo by Illiya Vjestica on Unsplash.

13. Making the Best of Our Current Landscapes

We should make the best of what we have and work with it. According to ecologist Ken Thompson, rather than trying to recreate a pristine past, we should focus on enhancing our current landscapes’ ecological resilience and biodiversity and instead “focus on getting the best out of our brave new invaded word”. It is difficult to have a full picture of what an original landscape actually looked like, even if we all agreed on how far we wanted to go back to recreate landscapes that continually changed over time–do we go back 1,000 years, 10,000 years, or more? Even if we had an accurate understanding of what these landscapes look like, some of the species (e.g., megafauna) holding a given landscape in that pristine balance are no longer there, so we cannot really recreate that original landscape. In regards to the existence of non-native species, scientists increasingly argue that their impact is vastly exaggerated and that they generally exert a negligible effect on biodiversity. These non-native species are likely taking advantage of instabilities caused by pollution, climate change, and habitat degradation, rather than being vectors of dangerous change. In any case, the ultimate question we should be asking ourselves is–should we focus our energies on conserving existing landscape by protecting or eradicating single species (e.g., non-native ones) or should we be open to let nature take us back to a more biodiverse world?

14. Naturalizing Rivers for Flood Resilience and Biodiversity

Naturalizing rivers and rewilding river catchments is a cheaper and safer way of creating resilience against floods. The British obsession with trying to remove water from the land as fast as possible dates back to the Victorians–according to the author, British farmers today have simply maintained and improved the drainage systems the Victorians put in place. These are maintained so they can receive water drained off the land by the intricate system of ditches and underground drains. The ultimate objective of these systems is that the water reaches the sea as quick as possible. Unsurprisingly, though, as soon extreme events appear on the horizon tragedy unravels in the form of dangerous floods. Instead, what is needed is to have water stay as long as possible on the land, which can act as a sponge that is able to receive large amounts of water, which can then be released slowly and safely. The filling in of canals at Knepp and returning its river to its floodplain has not only mitigated flooding downstream, but has also created huge opportunities for wetlands birds, flora, and invertebrates. Furthermore, marshy vegetation resulting from this change acts as a filter, purifying nitrate and phosphate run-off entering their land from intensive farming sites nearby.

15. How Keystone Species Like Beavers Re-Naturalize Rivers

Introducing keystone species can effectively re-naturalize river ecosystems and significantly boost biodiversity. For instance, introducing beavers in our rivers quickly adds complexity, naturalism, and efficiency to the water system, and is much cheaper than engineering projects trying to mimic the same outcomes. Beavers have shown across diverse geographies to be excellent at slowing and regulating water outflows over time, preventing streambed erosion and offering flood protection. Over the spawn of a few hours, beavers can build dams and convert overnight a small channel into a pond. In doing so, beavers literally breathe life into the land, increasing tremendously its biodiversity.

16. The Nutritional Benefits of Pasture-Fed Beef

Pasture-raised beef offers superior nutrition compared to intensively farmed alternatives, with a healthier balance of essential nutrients. Grain-fed animal fat can be detrimental to human health and is increasingly linked to obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, asthma, cancer, and other illnesses. In contrast, its pasture-fed counterpart presents not only a much healthier ratio of omega-3 to omega-6, but also higher levels of vitamin A, E, beta-carotene, or conjugated linoleic acid (CLA), which reduces body fat and the risk of heart attack. In regards to cattle’s critical role in driving climate change through GHG emissions, the author suggests as solution to simultaneously eat less meat and to return to less intensive traditional methods of rearing animals.

Photo by mana5280 on Unsplash.

17. The Dire State of Modern Agricultural Soils

Modern farming has reduced our soils to dirt, a sterile medium in which plants struggle to grow without fertilizers. Without soil organisms–such as earthworms–and soil structure to retain them water and nutrients leach away and the soil compacts and becomes susceptible to erosion. Earthworms and other important organisms such as bacteria, mycorrhizal fungi, protozoa, or nematodes are killed not only through the application of chemical fertilizers and pesticides, but also by tilling and other operations carried out with farm machinery that contribute to the compaction of the soil. The soil situation is so dire that some estimates suggest that there could be only about one hundred harvests left in the UK.

18. ‘Pop-Up Knepp’ Projects to Restore Degraded Agricultural Soils

“Pop-up Knepp” projects across the country could potentially restore soils across agricultural landscapes. Analogous to the role of fallow, a farming technique in which arable land is left without sowing for one or more vegetative cycles so it can recover, larger-scale rewilding of agricultural landscapes could take place for longer period of time, say twenty to fifty years. Once the land had fully recovered it could then be returned to agricultural production. This type of projects could be planned at a large scale, so as to assure the connectivity of lanscapes and allow to maximize biodiversity benefits. As things stand today, it is a matter of time before agriculture farms will have to be eventually abandoned anyway as soils continues to deplete–it seems like the time is ripe for bold forward thinking about existing alternatives.

19. The Impact of Childhood Nature Experiences on Environmental Advocacy

The decrease in nature-related experiences during childhood bears important consequences in attitudes towards the environment later on. Studies have shown that children who spend time in nature during ages 7 and 12 tend to view nature as a magical place. When they grow into adults they are more likely to be preoccupied by nature protection. This relation is worrisome, given that an increasing amount of kids’ time is spent indoors and dedicated to other interests. Although education certainly plays an important role as well in developing these sensibilities, just spending more time outdoors could go a long ways to ensure there are sufficient advocates for nature protection in decades to come.

20. Why ‘Wilding’ Might Be More Realistic Than ‘Rewilding’

Ultimately, this books offers hope but also demonstrates the complexity involved in attempting to rewild our landscapes. The author explicitly prefers to use the term “wilding” for their project, rather than “rewilding”, which denotes an attempt to return to a previous pristine condition that is both hard to ascertain and which raises a lot of debate (i.e., how far back do we go and whether there is sufficiently conclusive evidence). Furthermore, there are numerous cultural and regulation barriers to consider–particularly related to the introduction of the animals–that prevent a complete hands-off approach. As the author succinctly summarizes, “this is rewilding in the Anthropocene with footpaths and dog-walkers to consider”. She also transparently discloses their need to raise funds to support their biodiversity venture. Where possible, they engage in different enterprises that bring money to their project, from selling pasture-fed meat to creating a space for a small fishery. A “wilding” project (instead of rewilding) attempts to simply make the best of the current context and limitations. This flexible approach reminds the reader of the risks about being too radical about certain ideals and that, ultimately, what really matters is getting started and taking steps in the right direction–the path that tries to maximize biodiversity and to heal our rural landscapes.

*Affiliate link: If you enjoy our content, consider purchasing your book through our link. We earn a small commission, which helps support the blog. In addition, 10% of all revenue generated is donated to charitable causes.

Criticism:

Although most ideas that appear throughout this book are presented very throughly, I would have liked to see a more detailed description of counterarguments to the wood pasture hypothesis. It is convincingly presented as a closed case for the wood pasture camp. However, a quick search reveals that there is still a lively debate around this point.

The book claims that pasture-fed beef is sustainable. A lot of asterisks should be added to this claim. Indeed, from the point of view of biodiversity, introducing longhorn cattle has proven to be disruptive in the landscape in terms of increasing diversity. But from a climate perspective, the GHG emissions balance of their introduction is not discussed and no estimates are presented. Unfortunately, cattle emit very large amounts of GHG emissions through enteric fermentation, which are very unlikely to be balanced out by a smaller order of magnitude carbon sequestration that takes place in the soil and in some vegetation. In the author’s defence, though, she does ultimately advocate for a simultaneous reduction of meat consumption and for it to be pasture fed, which is a reasonable rationale. What is unlikely to be feasible is to maintain (or increase) current global meat consumption while switching to pasture-fed systems.

Finally, I would have appreciated more nuance in relation to describing where this type of wilding intervention is appropriate and where it is not. The authors do present examples of where this works outside of their project in some other countries; it would have been equally interesting to hear their perspective of its limitations, of where this approach does not work. I am thinking for instance about the Mediterranean basin forests and their recurrent challenges with fires. Surely, this “letting go” approach would be generally less viable there at the very best and could even be dangerous.

Conclusion:

This was a very engaging account of an incredibly interesting long-term biodiversity experiment taking place at Knepp. It offers a hopeful alternative to traditional approaches to nature restoration and I can’t wait to have the opportunity of visiting it. This book offers invaluable insights into rewilding and nature restoration, making it a must-read for anyone passionate about sustainability and biodiversity. Not only did it provide an answer to my initial questions, but it has also opened the door for many more. Ultimately, the reader will not only learn about the underlying dynamics that explain how we currently manage our land, but will also finish this book hopeful - there is an inexpensive and straightforward solution that may be applied to millions of hectares of unproductive land in Europe and elsewhere across the world to heal our landscapes and bring back our biodiversity.

Other reads to explore from the author:

Practical guide to rewilding: “The Book of Wilding: A Practical Guide to Rewilding, Big and Small” (affiliate link), by Isabella Tree

Check out other recent articles

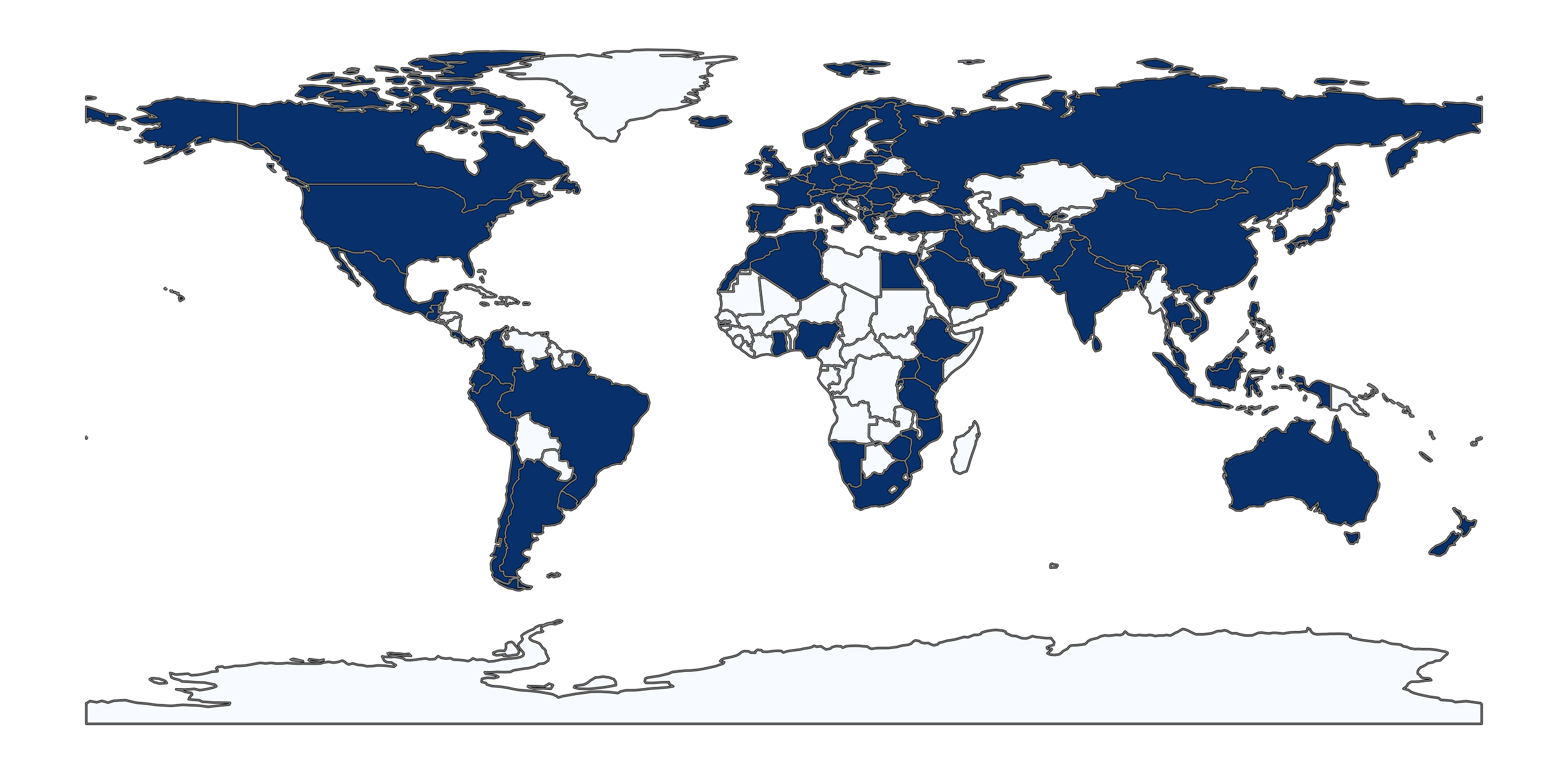

Join readers from more than 100 countries, subscribe below!

Didn't Find What You Were After? Try Searching Here For Other Topics Or Articles: