8 Surprising Lessons on Work and Time from Dr. James Suzman’s Research

Reading time: 11 minutes

How Work Has Shaped Our Use of Time Through History

Key Takeaways from Dr. Suzman’s Exploration of Work and Human History

Modern society increasingly seeks meaning and purpose through jobs and the work we perform. Work often defines social status and identity in our modern culture, and, for most of us, it is where we spend the majority of our time. The forty-hour week was already common in most manufacturing industries since the beginning of the twentieth century. Why then, in an era of unprecedented abundance, do we remain so preoccupied with scarcity and with working so hard?

Anthropologist Dr. James Suzman guides readers through an in-depth journey of human history that starts 300,000 years ago with the appearance of Homo sapiens. The book illustrates how our relationship with work has been shaped by historical events such as the mastery of fire, the advent of agriculture, our move to cities, or by the Industrial Revolution. Moreover, it assesses how a new automated revolution could affect our society and the potential dangers it poses to inequality. Suzman’s research reveals that our deep connection to work is a recent historical development and that for over 95% of our history we displayed a very different attitude towards work. How did this transition take place, to a world where we are obsessed with our jobs? And, if this is a recent turn of events, is there hope for building alternative relationships with how we spend our time?

*Affiliate link: If you enjoy our content, consider purchasing your book through our link. We earn a small commission, which helps support the blog.

Key Lessons on Work and Time from Human History

1. Humankind’s Missed Opportunity for Collective Leisure

Keynes predicted in 1930 that by our time economic growth, productivity improvements, and technological advances would bring us to the ‘promised land’, where everyone’s basic needs are met, and, therefore, nobody would have to work more than 15 hours. Even though we have more than surpassed Keynes’ growth projections, most of us work just as hard as our grandparents did. Moreover, our governments remain focused on pursuing economic growth and employment creation. Furthermore, in most developed countries younger generations are now expected to work longer than before to sustain aging populations.

Consider in contrast the lives of hunter-gatherer societies, who were not only well nourished, but rarely worked more than 15 hours a week, spending the rest of their time at rest and leisure. Isn’t here surely any insight we can learn from them here? Anthropologists studying today’s indigenous peoples, such as the Ju/'hoansi people of southern Africa, conclude that one of the reasons this was possible is that these societies cared little for status and accumulating wealth and focused on meeting their near term needs. Their life was organized around the presumption of abundance rather than scarcity.

2. Scarcity Economics: A Flawed Framework Driving Hard Work

One of the book’s main stated objectives with this book is to “loosen the claw-like grasp that scarcity economics holds over our working lives” and our corresponding “unsustainable preoccupation with economic growth”. Scarcity economics argues that human desires are limitless and resources are finite. Everything is scarce, since there are not enough resources to satisfy everybody’s wants. According to the author, this idea sits at the definition of economics as the study of how people allocate scarce resources to meet their needs and desires.

However, even if this underlying assumption is true today, it wasn’t true for the majority of the 300,000 years we have organized ourselves in society. There are plentiful examples of indigenous peoples today that prove that evolution has not inevitably molded us into “selfish creatures, burdened by desires we cannot satisfy”. It is not a built-in human trait. Rather, it responds to a relatively recent development in evolutionary terms that materialized itself in the Industrial Revolution. During this period, low classes could afford for the first time to set aside sufficient disposable income to buy the things that their factories were spitting out. Yet, to understand fully understand this change in mindset one has to go back further in time to the transition from hunter-gatherer to agricultural societies.

* Further Reading – Article continues below *

3. Agriculture’s Profound Impact on Human Labor and Time

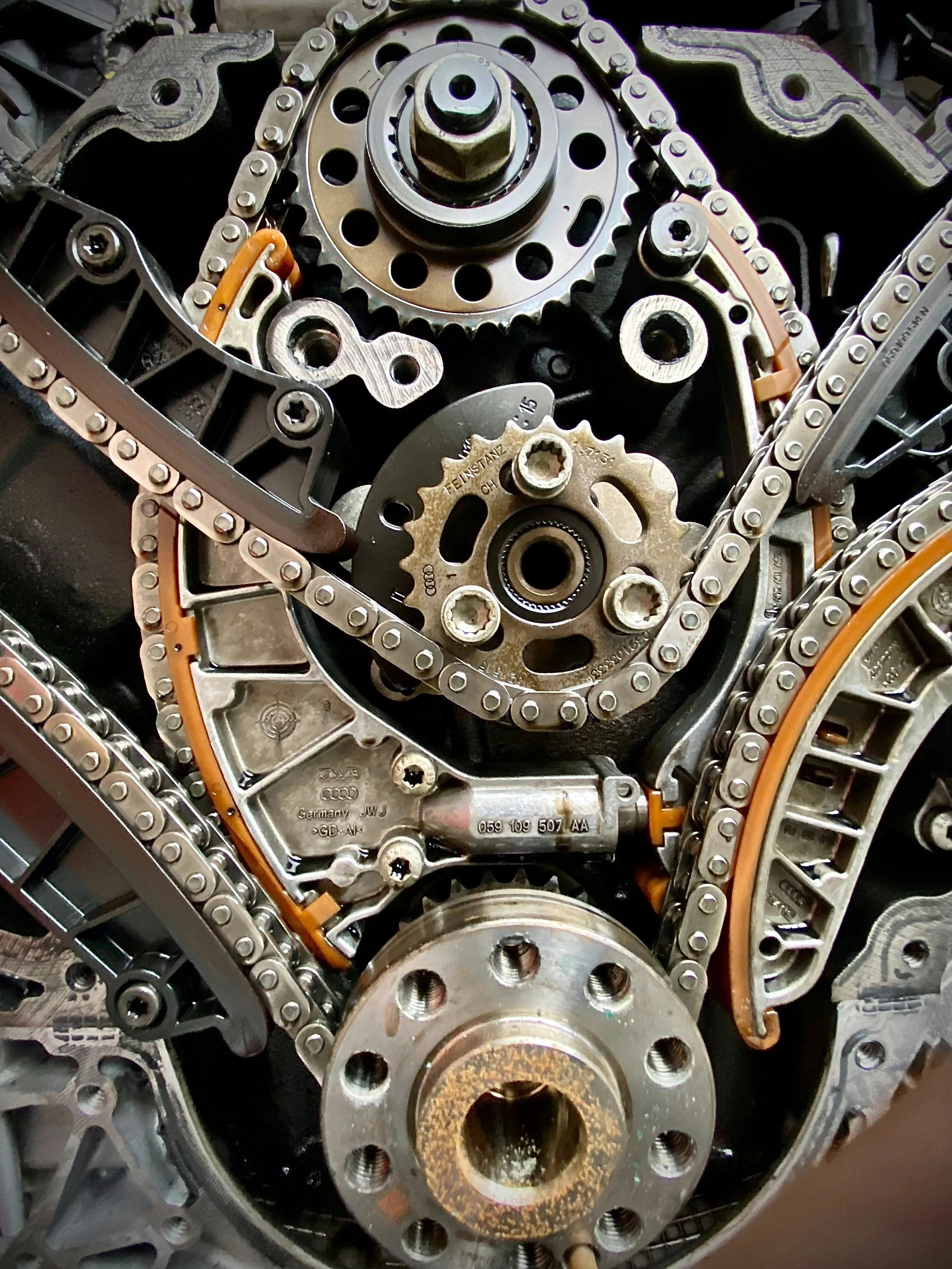

According to the author, today’s scarcity economics is directly tied to the appearance of agriculture. Experimenting with farming took place around 12,000 years ago, likely induced by climate change events. For the first time, farmers produced energy surpluses that allowed for populations to slowly increase, to settle in larger towns, and, eventually, even in cities. It is in these urban settings where we observe the first job specializations in our history.

However, the agricultural revolution imposed significant changes on human labor and well-being. Farming societies worked much harder (have you ever heard of a farmer working 15 hours per week?) and had lower life-expectancy than hunter-gatherer societies. Moreover, up until the Industrial Revolution, any gains in agricultural productivity were soon gobbled up by growing populations that could not be sustained. Known as the 'Malthusian trap,' this cycle drove an ongoing quest for new, fertile land and resources to till. As a result, prosperity was usually a fleeting thing, and scarcity was more common than in earlier hunter-gatherer societies.

These agricultural societies progressed in cycles, where productivity booms were routinely interrupted by times of depleted soils, diseases, famines, and conflicts, which were far less frequent for hunter-gatherers. Anxiety about scarcity was an intrinsic characteristic of farming societies that continues to underpin how we organize our economic life today. Agriculture changed our perception of time, from focusing on the present or immediate future to gauging future risk based on past experience. In a farmer’s eyes, the considerable work done to make a land productive meant the land owed them a debt, a harvest. It is not surprising that farmers then extended this concept of labor/debt to the relationships they had with each other.

Photo by Martin Kleppe on Unsplash.

4. Understanding Work Through Nature’s Lens: The Biological Urge to Stay Busy

A key goal of Suzman’s book is to uncover how our intrinsic relationship with work–in the broader expending energy sense–is more fundamental than economists think. The author uses south Africa’s black masked weaver (pictured below) as a perfect metaphor of how to explain human’s relationship to work and why we continue to appear as busy as ever.

In summer, male black masked weavers will build up to 25 near-identical nests, each of which can take up to a week to build. After each completion, the weaver proceeds to destroy it without an apparent reason, baffling observers. Local folklore in southern Africa holds that male weavers destroy a nest after it has been inspected by a female weaver and found it somehow wanting. However, this is not correct, since male weavers irrationally destroys many nests even before they have been inspected. Furthermore, research studies have concluded that the quality of the nest is not a key factor for the selection of the nest either–the female weaver ultimately gives a strong preference to a good location over anything else.

If the energy quest were critical here, wouldn’t male weavers have evolved to build one or two excellent nests in good locations, instead of expending tremendous amounts of energy in building and then destroying 25 nests? Interestingly, researchers studying black masked weavers have observed no focused foraging behavior by males at all, concluding that during the building season the food was so abundant that they casually foraged seeds, grains, and insects while retrieving materials for their multiple nests. What does all this have to do with humans and our work?

Black masked male weaver building its nest. Photo by Steve Evans.

Ultimately, the bird may build and destroy nests for no other reason than the fact that they have energy to burn. The author suggests that one of the ultimate reasons why we, as the black masked weaver, work with such profligacy is that when we have surplus energy, we may be expending it by doing work in compliance with the law of entropy. Could it be that our restlessness and overworking behaviour can be explained by physics–namely, by entropy and the second law of thermodynamics?

Biologists may find it unsurprising, given that many animal behaviors are shaped by energy abundance. Many hard to explain animal traits and behaviors have been shaped by the seasonal over-abundance of energy rather than by the battle for scarce resources. For instance, passerine birds that eat from bird feeders in gardens have been known to remain slim by increasing the intensity by which they sing, fly, and perform other routine behaviors. Could it be that humans continue to work very hard, in part, just because we also have a lot of energy to burn? In the same way that weavers use their surplus energy to build elaborate and often unnecessary structures, so have humans, when gifted with energy surpluses, have found creative ways to put it to work.

5. Endurance and Perseverance: Traits from Our Hunting Past

Humans possess a unique characteristic that sets us apart from other mammals: endurance. Whereas lions, cheetahs, and the like hunt through short, powerful sprints or bursts of energy, humans evolved using a very different strategy. We are proficient long distance runnersæ–capable of keeping a steady, unrelentless pace for hours if necessary–thanks to our ability to sweat and cool down.

Our ancestors would select a suitable prey, then pursue it slowly yet relentlessly over the course of many kilometers. The hunter would not allow the animal to rehydrate or cool down and persevered in this fashion until, eventually, the animal gave up. The hunter could then approach the animal and literally suffocate it with its own hands. Hunting in this way may have played an important role in building up the perseverance, patience, and sheer determination that still characterize our approach to work today.

6. The Perils of Infinite Aspiration and the Need for Restraint

As observed by Marshall Sahlins, “wants may be easily satisfied either by producing much or desiring little”. Hunter-gatherer societies that enjoyed large amounts of leisure and only worked 15 hours per week may have achieved this through living by a different set of values and by not seeking the accumulation of wealth and status. The book describes numerous mechanisms, including light mockery, that tribes use for keeping the community members’ ego–particularly for hunters–in check and that guard the egalitarian nature of the community. Foragers’ attitudes to work were not only a reflection of their confidence in the providence of their environment, but also sustained by social norms and customs that evenly distributed food and material resources.

Since humans have gathered in cities, our ambitions have been moulded by a different kind of scarcity compared to subsistence farmers or foragers, a scarcity that is defined by aspiration, jealousy, and desire rather than absolute need. This transition was facilitated by moving from tightly-knit communities with strong social ties and intolerant of any form of inequality to large urban settlements were it is harder to bind people together, and where dislocation and anxiety can produce antisocial behavior.

Today many people are driven to work long hours to gain social status and keep pace with peers. Although this likely originated from our move to urban settlements, it was certainly intensified during the Industrial Revolution, where for the first time, workers had sufficient purchasing power to consume the goods that their own factories were spitting out, closing the loop between production and consumption. After the Second World War, the appearance of aggressive advertising blurred out our ability to distinguish between absolute and relative needs. If we are not careful, our wants can truly become infinite, and are another key factor explaining why we continue to toil so hard in an era of so much abundance. With the proliferation of social media and platforms such as Instagram and Facebook this ‘malady of infinite aspiration’ is easier to catch than ever.

The author cites experiments of working fewer hours, for instance that of the Kelloggs company, which instated a 30 hour work week in the 1930s. The 30-hour week at Kellogg’s continued until the 1950s, when employees chose to return to a standard 40-hour workweek: they wanted more money to purchase the endless procession of consumer products entering America in the post-war era.

Advertising and busy people in Times Square, New York City. Photo by Cris Tagupa on Unsplash.

7. Rising Inequality and the Consequences of Economic Growth

For much of the twentieth century, there was a close relationship in industrialized countries between labor productivity and wages. In other words, as the economy grew and labor output increased, so did the take home pay of its workers. This changed in 1980, an event referred to as the “Great Decoupling”: while productivity and economic growth continued to increase, wage growth was stalled for the vast majority of citizens. For many economists, this decoupling was the first evidence of technological expansion contributing to the concentration of wealth in fewer hands.

In 1965, CEOs in the top US companies took home twenty times the pay of an average worker. By 1980, this had increased to thirty times, and by 2015 it had surged to nearly three hundred times. Interestingly, surveys carried our in the US reveal that most people underestimate the pay ration between bosses and unskilled workers by more than a factor of ten. Since the Great Decoupling, the top 1% of people globally has captured twice as much wealth as the rest of the population combined. The author argues that there is an enduring public illusion of greater material equality, consequence both of the perseverance of the incorrect notion that there is a correspondence between wealth and hard work–a legacy from the agricultural revolution–and also because the poor want to keep the dream alive of achieving financial success for themselves.

Suzman warns that the impending wave of automation poses risks to inequality and job stability. He expects inequality to rise also across countries. Over the last decades, inequality between countries had decreased as poorer countries with low wages attracted a larger share of the global manufacturing industry. However, given that, unlike wages, the cost of technology is similar everywhere, automation is expected to stop or reverse this trend.

8. “Bullshit Jobs” and the Future of Meaningful Work

David Graebers famously coined the term “bullshit job” as “employment that is so completely pointless, unnecessary, or pernicious that even the employee cannot justify its existence”, stating that “it is as if someone were out there making up pointless jobs just for the sake of keeping us all working”. This seems to resonate well with public opinion. A Gallup report revealed that very few people find their work meaningful or interesting.

Data collected across 155 countries during 2014-2016 revealed that only 15% of employees world wide are engaged in their job, two thirds are not engaged, and 18% are actively disengaged. These numbers are startling and enough to spark some inner soul-searching, particularly if all our hard toil is just, like the black masked male weaver’s toil, for the sake of burning energy, or, worse still, for the sake of keeping up with the Joneses. No wonder so many people quietly disengage from their roles—a modern pattern often described as “quiet quitting”—when work feels disconnected from purpose or meaning.

The rise of the service sector in the twentieth century is proof of our ability to creatively produce new types of jobs to accommodate those ejected from traditional production lines. Yet, we don’t seem to be very proficient at designing jobs people are likely to find meaningful or interesting. This is acutely relevant, since the next wave of automation is already on our doorstep: some research suggests that up to 47% of jobs (in the US) are at high risk of being automated as early as 2030.

Keynes imagined a future where everyone’s basic needs were met and inequality had become irrelevant. Only the foolish would do more work than was needed, and, like a foraging society, perhaps would even receive ridicule rather than praise. Keynes wrote: “The love of money as a possession–as distinguished from the love of money as a means to the enjoyments and realities of life–will be recognized for what it is, a somewhat disgusting morbidity, one of those semi-criminal, semi-pathological propensities which one hands over with a shudder to the specialists in mental disease.”

Thirty years later, John Kenneth Galbraith insisted that the transition to an economics of abundance would be organic and shaped by individuals rejecting the pursuit of wealth in favor of worthier work. According to Dr. Suzman, a shift away from wealth-focused work is already in motion: Gen-Z and millennials in industrialized countries insist on finding work they love, rather than—as their grandparents did—learning to like the work they find.

*Affiliate link: If you enjoy our content, consider purchasing your book through our link. We earn a small commission, which helps support the blog.

Did you enjoy this post? Don’t miss our insights on the current status of global job satisfaction or on how to best navigate the tradeoffs between career and money.

🌿 Thanks for reading The Good Life Journey. I share weekly insights on money, purpose, and health, to help you build a life that compounds meaning over time. If this resonates, join readers from over 100 countries and subscribe to access our free FI tools and newsletter.

👉 New to Financial Independence? Check out our Start Here guide—the best place to begin your FI journey.

About the author:

Written by David, a former academic scientist with a PhD and over a decade of experience in data analysis, modeling, and market-based financial systems, including work related to carbon markets. I apply a research-driven, evidence-based approach to personal finance and FIRE, focusing on long-term investing, retirement planning, and financial decision-making under uncertainty.

This site documents my own journey toward financial independence, with related topics like work, health, and philosophy explored through a financial independence lens, as they influence saving, investing, and retirement planning decisions.

Check out other recent articles

Join readers from more than 100 countries, subscribe below!

Didn't Find What You Were After? Try Searching Here For Other Topics Or Articles: