Feeling Life Has No Meaning? A Relativist’s Answer to Nihilism

Humans have searched for meaning ever since they started looking up at the sky. Photo by Greg Rakozy on Unsplash.

Reading time: 10 minutes

The Meaning of Life: From Ancient Philosophy to the Age of AI

Introduction: Why We Ask About Life’s Meaning

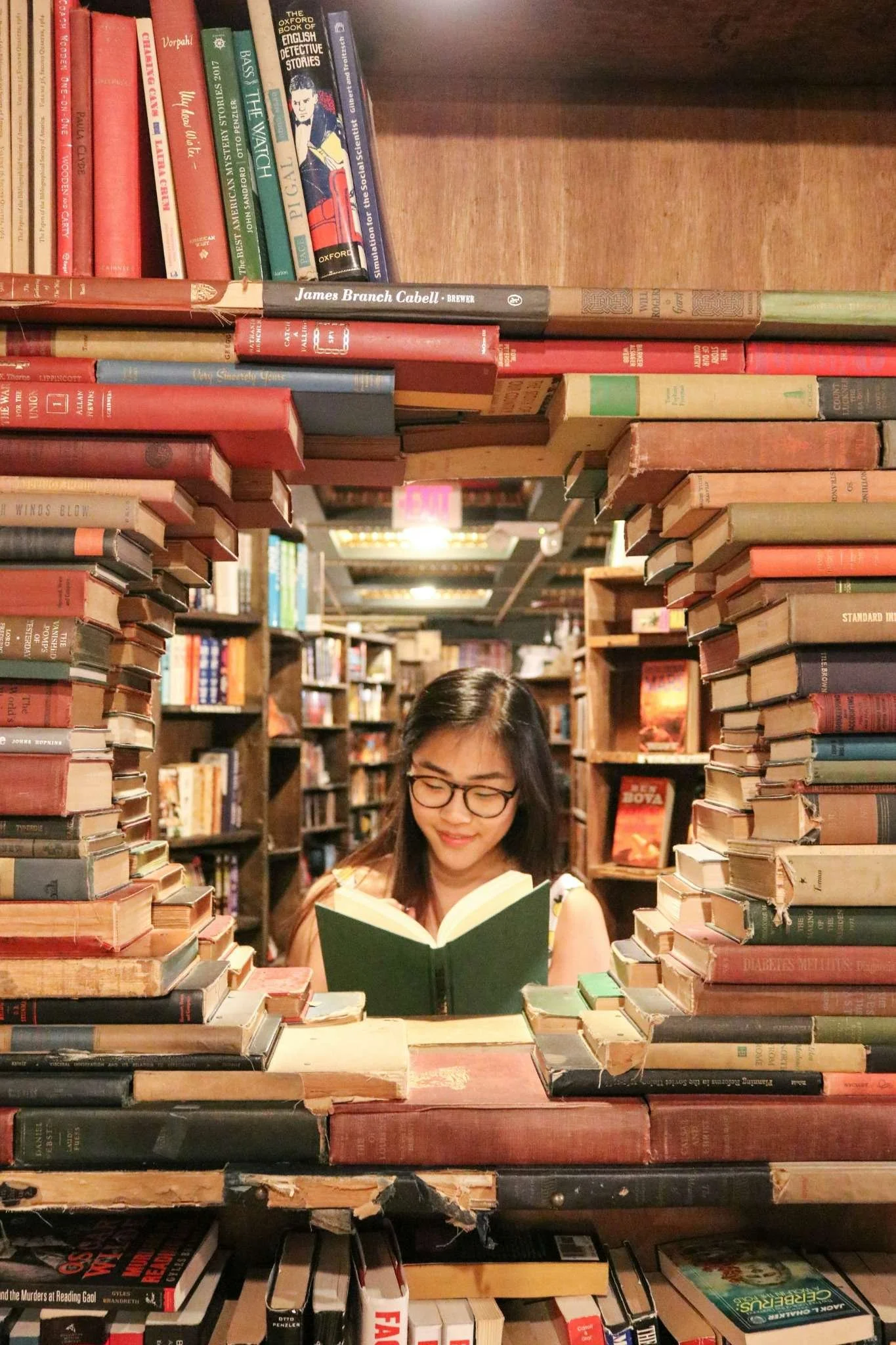

“What is the meaning of life?” People have been asking this very question for centuries, often in moments of doubt or when life feels somehow fragmented. If you’ve ever thought life feels meaningless or wondered whether it’s okay to feel that way—you’re certainly not alone. At the end of the day, we’re all just trying to find peace and joy in life.

This article explores a relativist perspective—the idea that life’s meaning is not fixed or eternal, but is constantly shifting across time, culture, and technology. Far from being nihilistic, this view can be freeing—allowing us to create meaning here and now, without fear of missing out on some hidden truth.

The persistence of this question suggests there may be an issue in how we are posing it. Perhaps the “meaning of life” isn’t something fixed that is waiting to be discovered—like a buried treasure—but something that evolves across cultures and eras. From this perspective, the absence of a single answer is not nihilistic but liberating—it makes meaning flexible, adjustable, and practical.

This is the perspective we’ll explore today—a relativist’s view on the meaning of life. First, let’s clarify what is not meant here by “relativism”, given that relativism has many branches and can be interpreted differently depending on context. We’re not talking here about moral relativism (e.g., what’s right or wrong) or epistemic relativism (e.g., truth is relative), or any other form of relativism.

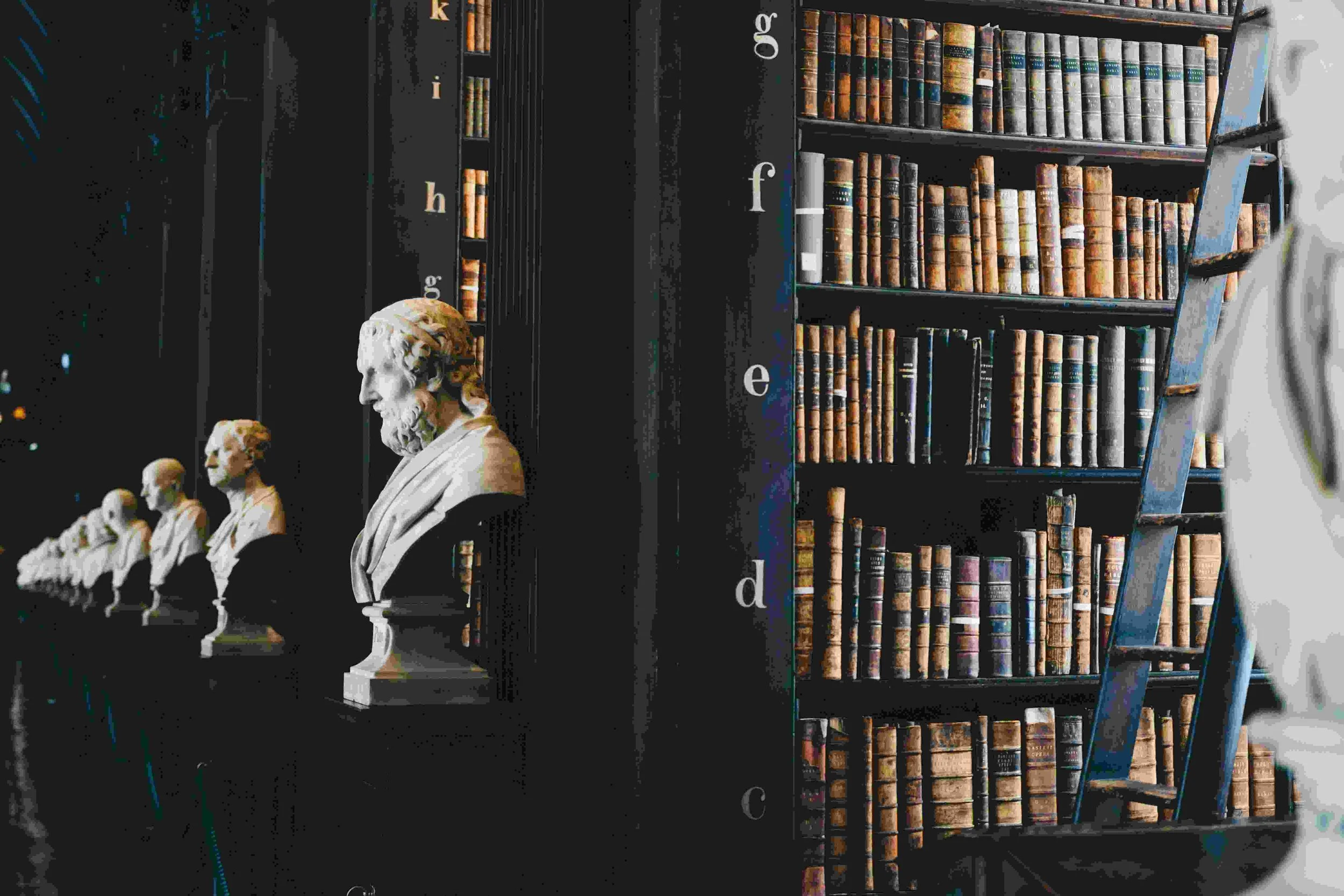

“What is the meaning of life?” has been asked constantly across eras, but the answer provided was always different across time and culture. Photo by Giammarco Boscaro on Unsplash

Instead, our focus here is on historical and cultural relativism—the idea that what counts as “the meaning of life” depends largely to the age and society in which one is asking the question. As we’ll see further on, the question and answer itself is unlikely to bring forth an absolute answer, but is instead a reflection of the historical context we live in.

In my view, recognizing this relativity doesn’t make the question irrelevant—it helps reduce existential angst. If there is no single eternal meaning, then we don’t need to worry about missing it. Instead, we “only” need to focus on constructing a meaning that works for us, here and now.

Psychology supports this approach. Think of Viktor Frankl, the famous psychiatrist who survived Nazi concentration camps. As written in Man’s Search For Meaning, Frankl argued that humans can endure almost anything if they perceive it as meaningful. From this lens, the value of meaning isn’t that it is absolute, but rather that it is functional to each one of us.

It orients us and—in extreme situations—can keep us alive. The question then becomes not “What is the meaning of life for everyone?” but what meaning we create for ourselves—in our current time and culture—that allows us to flourish and experience a sense of fulfillment.

Meaning is not something to be discovered, it’s something we build. Photo by NEOM on Unsplash.

Relativism and Meaning: A Shift in the Question

Relativism reframes the central question in a subtle but important way. Instead of asking “What is the meaning of life”, it asks “What meaning do we make right now?” This shift takes away the pressure of trying to find an ultimate answer and replaces it instead with a more dynamic and participatory angle.

Meaning is not something discovered—it’s something we build. If you’ve ever wondered “Why am I struggling to find meaning in life?”, the relativist view suggests the problem isn’t you—it’s that meaning is always created, not found.

We shouldn’t see this lack of universal meaning as a tragedy—I personally see it as a liberation. If there is no singular essence to life, then we’re free to pursue what feels meaningful to us, without some cosmic-level FOMO. My fulfillment doesn’t need to look like yours, and society’s mainstream vision of purpose—largely defined around work—doesn’t need to define mine.

Consider how different cultures have answered the question of meaning within the same historical era. In the 20th century, meaning in the US was often framed around personal freedom, civil rights, and individual achievement. At the same time, in the Soviet Union meaning was presented in collective terms—to serve a revolution, the state, or the people.

Both cultures overlapped in time and provided radically different answers to their people—it’s clear that the question has no one-size-fits-all answer. And as we’ll see in the next section, when we zoom out further across history, the diversity of answers only becomes larger.

Relativism aligns naturally with how humans actually live. We are constantly negotiating meaning through social rituals, art, politics, or relationships. It is constantly changing as our culture evolves. Technology, social norms, and collective challenges all influence the answer. If life’s meaning is relative, then it exists less as an answer and more as a reflection or mirror of our time.

Berlin Wall, Berlin. For some time, meaning was literally answered differently depending on what side of an artificial boundary you lived in. Photo by Lily on Unsplash.

How the Meaning of Life Changed Across Eras

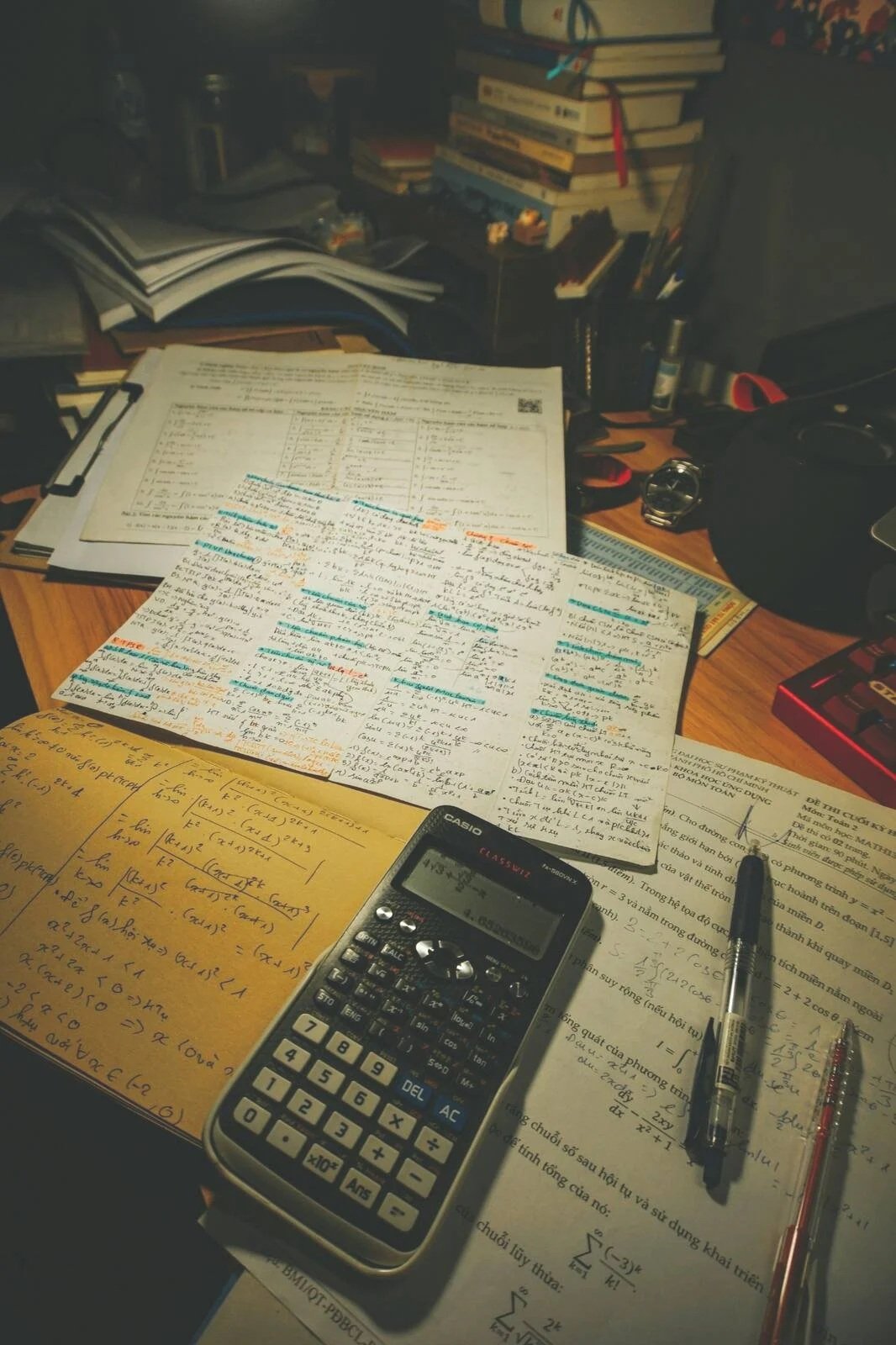

Still not convinced on the relativist’s approach to the meaning of life? Consider how the question has changed across time—depending when it was asked in Western culture. In Table 1 below, we provide some examples of how the dominant source of meaning changed across eras. These different answers are not only the product of abstract speculation—but reflect material conditions, religious frameworks, social needs of the time, and—crucially as we’ll explore later—technology.

For example, in Ancient Greece, meaning was often tied to philosophy—think about how the Stocis argued that a good life comes from rational judgement, virtue, and living in alignment with our nature. By the Medieval era, meaning was almost entirely about the service of God—whether through monastic devotion, labor in the fields framed as some form of divine duty, or participation in the Crusades.

During the Age of Exploration, purpose was found in adventure, conquest, and spreading empire and faith—sailors, soldiers, and missionaries framed their own struggles as part of a larger, honorable mission. The nation-building and Colonial era also brought a sense of patriotism and duty to empire or nation, where life’s meaning often lay in service of political expansion.

Acropolis, Athens, Greece. Ancient Greece is often seen as the cradle of Western philosophy. While earlier thinkers speculated about nature, Socrates is considered the first major philosopher who shifted the focus to how we should live. Photo by Constantinos Kollias on Unsplash.

Turn to the Industrial 18th century, and productivity, science, and progress become central, reflecting optimism in Enlightenment ideals. By the 20th Century, the search for meaning gravitated towards material comfort, personal freedom, and self-actualization—think of the “American Dream” or the civil rights struggles.

Finally, in the 21st century, meaning often looks like an individual project—self-expression, digital identity, and constant optimization. Technology is both enabling and pressuring us to measure every aspect of life in an increasingly connected way. We may even be at the beginning of a deeper shift—where AI-driven transformations could soon redefine how we answer the question entirely.

It’s clear that meaning is rarely timeless, but bound to the conditions and context of our time. Of course, this quick overview has focused only on the West. If we looked globally—say at philosophical traditions in East Asia, which emphasize harmony and family duty—the variety would be even richer. That only reinforces the relativist point: meaning is inseparable from culture.

Table 1: Summary of how “the meaning of life” question has changed across time in the West.

| Era | Dominant Source of Meaning | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Ancient Greece | Philosophy, rational judgment, living in alignment with nature | Stoicism: virtue, reason, and harmony with nature |

| Medieval Europe | Service to God, religious devotion, labor as spiritual duty | Monastic life, fieldwork as divine service, Crusades |

| Age of Exploration | Adventure, conquest, spreading empire and faith | Columbus, Magellan, missionary zeal |

| Colonial / Nation-Building | Patriotism, service to empire or nation | "Civilizing" missions, national expansion |

| 18th–19th Century Industrial | Progress, productivity, science | Factories, Enlightenment optimism, Darwin |

| 20th Century West | Material comfort, freedom, self-actualization | American Dream, civil rights, consumer culture |

| 21st Century | Individual self-expression, digital identity, optimization | Wellness, personal branding, data-driven living |

Philosophical Frameworks: What previous Thinkers Have Said

As illustrated in Table 2 below, formal philosophical thought has also offered very different frameworks for answering life’s big questions over time, with many providing not only an answer but also a method for living.

Socrates argued that “the unexamined life is not worth living.” For him, life’s meaning lay in constant questioning, self-reflection, and the pursuit of wisdom. To live well meant to know yourself and seek truth above all else—even if it was uncomfortable.

For Aristotle, life’s meaning was found in eudaimonia—flourishing through virtue and the cultivation of good character. In practice, meaning came from living a good life: developing your strengths, treating others fairly, and striving to become the best version of yourself.

The Stoics—like Seneca, Epictetus, or Marcus Aurelius—believed meaning came from rational judgement, virtue, and living in harmony with nature. Ultimately, they advocated for cultivating resilience, focusing on what’s in our control, serving others, and responding to challenges with integrity.

“There is only one way to happiness and that is to cease worrying about things which are beyond the power of our will.” Epictetus. Image from Wikimedia

Christian thinkers like Aquinas and Augustine shifted the meaning answer to God. Life’s meaning was to serve God faithfully, seek salvation, and align earthly duties with divine purpose. For many believers today, this idea still remains central—service to something larger than oneself.

Nietzsche shattered that certainty—or at least expressed what was already happening. He argued that life has no inherent meaning at all—“God is dead”—and that humans must create their own values. The message was radical but empowering—we build meaning for ourselves.

Existentialists like Sartre and Camus continued this line of thought. Life may be absurd and meaningless at its core, but at the same time freedom and responsibility give us purpose. The challenge is to embrace freedom without despair. In modern life, this could mean taking ownership of our choices and find meaning in how we live, not in fixed answers.

Again, the takeaway is that meaning is rarely timeless, but always evolving—where are we today and where will it take us next?

Table 2: Philosophical frameworks and their answers to the meaning of life, from Socrates to Existentialism.

| Philosophy | Answer to Meaning of Life | Key Figures |

|---|---|---|

| Aristotle | Flourishing (eudaimonia) through virtue | Aristotle |

| Socratic | The examined life, pursuit of wisdom | Socrates |

| Stoicism | Rational judgment, virtue, alignment with nature | Marcus Aurelius, Epictetus |

| Epicureanism | Simple pleasures, friendship, absence of pain | Epicurus |

| Christianity (medieval) | Service to God, salvation | Augustine, Aquinas |

| Nietzsche | Life has no inherent meaning; create values | Nietzsche |

| Existentialism | Freedom, responsibility, embrace absurdity | Sartre, Camus |

With this variety of philosophical answers in mind, how do most actually answer the question today?

Modern Views: What We Say About Meaning Today

And so we arrive to today. Although many religious traditions persist today and align their response to the service of God, most secular Western cultures’ answers to life’s meaning are no longer framed in terms of divine purpose. Instead, people tend to cite some combination of “happiness”, peace of mind, freedom, family, creativity, personal growth, and self-actualization. They tend to be deeply individualist responses—reflecting our cultural era’s emphasis on self-expression and personal choice.

Psychology science has reinforced this shift. Think of popular frameworks such as the PERMA model (Positive emotions, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, Accomplishment). Rather than looking upward to God or outward to nation or empire, modern people look inward towards emotional wellbeing and personal fulfillment as the place where meaning is built.

Of course, it’s not uniform—meaning today is also fragmented along cultural lines. In many parts of East Asia answers tend to emphasize collective harmony and family duty rather than individual self-expression. Someone in California might frame purpose as “discovering and expressing my true self”, while someone in Japan might point to “living in balance with family and society”. Again, same era, but very different answers shaped by culture.

Even today, meaning is embraced differently across cultures. Japan and other East Asian countries offer less emphasis on the individual than other western cultures. Photo by Sorasak on Unsplash.

Today, the very abundance of choice can lead to what psychologists call the paradox of choice: too many possible paths to fulfillment can feel overwhelming. On top of that, a hyperconnected world is reminding us in real time of what everyone else is up to, making it difficult for us to even come up with our own genuine answers.

At the same time, I think people are generally asking the wrong question. Today, people tend to (indirectly) ask themselves “What do I want in life?”, focusing too much on material comfort, career, or achievement. These are just good things to have in life. Unfortunately, they are avoiding the more difficult question of “What do I want out of life?” In other words, what philosophy of life do you espouse? How will your life reflect your values and lifestyle preferences?

The “in life” focus can easily slide into consumerism, where meaning gets equated with status symbols, lifestyle upgrades, or career milestones. These do provide temporary satisfaction, but don’t endure once the novelty fades away. In contrast, the “out of life” question pushes us to go deeper and engage in philosophy.

I’ve felt this myself: upgrading my lifestyle—a new gadget, a larger flat—only to find the excitement fades very quickly. Perhaps what I really needed wasn’t another “in life” comfort, but a deeper sense of what I wanted out of life.

In some way, the challenge for modernity is not that we lack options, but that we’re too distracted to face the deeper questions entirely. What we want in life is rarely enough unless it aligns with what we want out of life. This failure to ask the deeper questions leaves many chasing after consumer comforts and career milestones, only to feel unfulfilled. In many ways, modern consumer culture distracts us from philosophy.

77% of global employees don’t find meaning nor engagement in their job. But many of us are still somehow culturally obsessed with our careers. Photo by Israel Andrade on Unsplash.

Technology Redefines Meaning: Bryan Johnson’s Relativist Thesis

Technology doesn’t just change what we can do, it also changes what we believe life is for. Bryan Johnson, in the podcast that originally inspired today’s reflection, argues that the answer to the meaning of life is also deeply tied to technology.

Past technological revolutions reshaped life’s purpose: the printing press democratized scripture and gave rise to Protestantism; electricity fueled a culture of progress and productivity; and the internet created a world of global self-expression. Technology is very much a part of the discussion.

Today, many see us already in the midst of another revolution—the age of algorithms and AI. A lot of it can be extremely positive. Like we recently covered, algorithmic living can be hugely beneficial in some areas (e.g., health), freeing up our minds for more creative pursuits.

In Johnson’s provocative Nietzschean twist, “the mind is dead”, what he means is not that we stop thinking, but that our minds are often deeply unreliable guides—wired for short-term gratification, prone to self-sabotage, and easily overwhelmed by modern input. It turns out our mind isn’t only doing a poor job, but may never have had our best intentions at heart.

In this view, the mind should no longer have a final say in every single decision that affects us. Instead, in some areas, well-designed systems and personal algorithms can make healthier and wiser choices on our behalf. It you’re jaw just dropped after reading this, I highly recommend reading our detailed article on this concept and of algorithmic living in general. Of course, it doesn’t have to apply to all aspects of life.

Our lives are already influenced by algorithms. So much of our free time, entertainment, and consumption is already determined by external algorithms—designed by others generally for their benefit, not yours. Instead, algorithmic living allows you to reflect and set your own systems in place before others set them for you. Photo by Vardan Papikyan on Unsplash.

In relation to today’s question, the slow implementation of algorithmic living may force humans—once again—to redefine what makes life meaningful beyond our cognition functions. Whether or not we fully agree with Johnson’s thesis, it does highlight how unstable our conceptions of meaning really are if they’re already shifting in front of our eyes.

What we tend to call “life’s purpose” is often only a reflection of our currently available tools. As we saw earlier, in an agricultural age, meaning was tied to the fields and the seasons. In a digital age, it’s tied to information and identity. If the mind truly is “dead”, perhaps life’s meaning will shift next—away from information and knowledge toward judgment, wisdom, or even how we design the systems and algorithms that shape our lives.

If the mind itself can’t always be trusted, and if technology keeps reshaping what we think life is for, perhaps the answer lies not in chasing something new but in turning back to wisdom that has demonstrated to be timeless across eras. One philosophical tradition in particular—Stoicism—seems surprisingly well-suited to guide us into this AI era of shifting meaning. Let’s explore how.

Seneca committing suicide with his foot in a bath. Coloured engraving by B. Ravenet after R. Earlom after Luca Giordano. Retrieved from Wikipedia.

Looking Ahead: Stoicism and the AI Era

If technology reframes meaning, then we’re clearly entering a new era. AI and automation are quickly affecting not only physical labor—as was originally expected—but also creative and white collar jobs. What happens when activities we once linked to meaning become automated? Does this render life purposeless, or, rather, push us to discover something deeper?

One option could be that humans return to being “generalists”. If AI can provide detailed expertize on demand, we may no longer need to devote our lives to narrow specialization. We may instead explore, learn more broadly, and refine judgement to decide on what matters. In this coming world, skills may matter less than wisdom and judgement. The capacity to discern—to choose well amidst overwhelming options—may become a defining human trait.

This is why I think Stoicism offers one of the most robust frameworks moving forward. The Stoics define human purpose as rational judgement—using our capacity for reason to guide how we live and act. Unlike productivity or conquest, this definition does seem timeless.

It does not depend on whether humans farm fields, run factories, or wield algorithms—judgment remains necessary in every context. The more saturated our world becomes with data and tools, the more valuable sound judgment will be.

Stoicism also grounds meaning in something stable but flexible. You don’t need to know “the meaning of life” in universal terms; you only need to know what is within your control, what virtue requires, and how to live with integrity in the present moment.

In plain terms: focus on what you can actually influence, act with fairness and courage, and don’t waste energy on what’s outside your hands. Stoicism doesn’t deny that meaning can vary, but it does offer a compass for navigating those shifting landscapes.

Wisdom and good judgment could become discerning traits in the age of AI. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

Conclusion: A Relativist’s Comfort

As we’ve seen, the search for the meaning of life may never yield a single universal answer. History shows that each era created its own, and this will likely continue in the future. Philosophy offers us a menu of frameworks to understand and navigate our era, rather than a final truth.

Relativism should not doom us to nihilism. In fact, I think it offers a healthier alternative for anyone asking “Is it okay to feel life is meaningless?” The answer is yes—and it’s a signal to start creating meaning that fits your time and circumstances.

It frees us to recognize that meaning is always constructed, always lived, and always shaped by culture and technology. What felt meaningful in one society or century may not resonate in another—and that’s not a failure but the nature of the question itself.

If the meaning of life is relative, then we are co-authors, not just recipients. This should in some way feel comforting, because we don’t need to fear missing out on one “real” meaning—there simply isn’t one.

Stoicism’s emphasis on rational judgement may become especially relevant as AI and automation changes how humans interact with the world. What will remain essential is how we choose. Technology may transform our tools, but applying wisely the virtues of courage, justice, and self-control remain timeless. The meaning of life may be no eternal essence but the enduring practice of exercising wisdom, virtue, and embracing the unique possibilities of our own time.

And as Viktor Frankl reminded us, meaning is never handed to us from outside—it emerges from how we respond to life. That is true in every age, and it will be true in the one we are now entering too.

💬 I'd love to hear your thoughts—how do you deal with lifestyle inflation and lifestyle creep? Please let us know in the comments!

🌿 Thanks for reading The Good Life Journey. I share weekly insights on money, purpose, and health, to help you build a life that compounds meaning over time. If this resonates, join readers from over 100 countries and subscribe to access our free FI tools and newsletter.

👉 New to Financial Independence? Check out our Start Here guide—the best place to begin your FI journey.

Don’t miss our article on 25 Stoic Principles for Joy and Inner Peace or the post where we discuss Bertrand Russell’s advice for a happy life.

About the author:

Written by David, a former academic scientist with a PhD and over a decade of experience in data analysis, modeling, and market-based financial systems, including work related to carbon markets. I apply a research-driven, evidence-based approach to personal finance and FIRE, focusing on long-term investing, retirement planning, and financial decision-making under uncertainty.

This site documents my own journey toward financial independence, with related topics like work, health, and philosophy explored through a financial independence lens, as they influence saving, investing, and retirement planning decisions.

Check out other recent articles

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

-

Not at all. Relativism doesn’t say “life is meaningless,” it says meaning isn’t fixed or universal. Instead, it changes depending on culture, history, and individual perspective. That can feel liberating rather than despairing—because it frees you from chasing one ultimate truth and lets you co-create meaning in a way that fits your context and values.

-

Nihilism claims there is no meaning whatsoever, often leaving people with a sense of emptiness. Relativism argues the opposite: that there are many possible meanings, each valid within its own context. Rather than stripping life of purpose, it invites us to build meaning actively—through choices, relationships, and philosophies that fit our moment in history.

-

The article traces meaning primarily through the Western tradition (from Ancient Greece to modern AI) because it’s the most familiar to me. But that’s only part of the story. If we expanded globally—to Confucianism in China or Hindu philosophy in India—we’d see even more diversity. That only strengthens the relativist claim: meaning is inseparable from culture.

-

Philosophy doesn’t provide a single eternal answer, but it offers frameworks. Aristotle taught that meaning comes from flourishing through virtue; the Stoics focused on rational judgment and resilience; existentialists like Sartre emphasized freedom and responsibility. Each framework reflects its time while also providing tools we can still use to orient our lives today.

-

Modern society often pushes us to ask “What do I want in life?”—usually answered with possessions, career milestones, or comfort. These things are nice but fleeting, since novelty fades quickly. The deeper question—“What do I want out of life?”—forces us to think about values, purpose, and philosophy. Without asking it, we risk chasing distractions and still feeling unfulfilled.

-

Technology has always reshaped meaning: agriculture tied life to seasons, the printing press tied it to scripture, and the internet tied it to self-expression. Today, AI and automation are shifting it again, questioning whether human purpose lies in labor, creativity, or something deeper. Meaning evolves with our tools—so part of our task is learning how to orient ourselves within each new landscape.

-

Stoicism defines human purpose as exercising rational judgment and virtue. Unlike other frameworks, it doesn’t depend on specific technologies, economies, or jobs. Whether humans are farming, working in factories, or living with AI tools, we still need wisdom, courage, fairness, and self-control. Stoicism gives us a timeless compass for navigating a rapidly changing world.

-

Frankl, a Holocaust survivor, showed that people can endure extreme suffering if they find personal meaning in it. His insight is crucial: meaning doesn’t have to be cosmic or universal to matter—it can be deeply personal and functional. This supports the relativist view that meaning is constructed, not discovered, and proves it can be life-saving in the harshest conditions.

-

Much of existential anxiety comes from fearing we’ll miss “the one real meaning” of life. Relativism dissolves that pressure by showing there is no single truth to miss. Instead, we’re free to build meaning in our current time and culture. This makes life less about hunting for a buried treasure and more about shaping a practice of living that fulfills us.

-

The key point is that meaning is not fixed, eternal, or universal—it shifts with culture, technology, and individual choice. That doesn’t make life meaningless, but dynamic. The challenge isn’t to uncover a final answer, but to live wisely and intentionally in our moment—choosing values and practices that let us flourish today, while staying open to change tomorrow.

Join readers from more than 100 countries, subscribe below!

Didn't Find What You Were After? Try Searching Here For Other Topics Or Articles: